By Ben Signor

On the cold night of 5 August 1944, a thousand Japanese prisoners of war at the Cowra Detention Centre in NSW attempted one of the largest and most audacious breakouts in history. It would come to be known as the Cowra Breakout, and the only battle to take place on Australian soil during the Second World War.

Five Australian soldiers and 230 POWs lost their lives in the battle, as the Japanese first tried to take the camp before fleeing into the surrounding bushland. Those POWs that weren’t killed were eventually recaptured.

Mat McLachlan is a battlefield historian who has made it his mission to uncover this oft forgotten chapter of Australian WWII history. It has been 78 years since the battle took place, and Mat has commemorated the anniversary by writing and releasing a new book – Cowra Breakout.

The book details the events that unfolded during and after the breakout, as well as the history of the Cowra Detention Centre, the motivations of the POWs, and the lives of some of the Australian Japanese soldiers involved.

More than 80 people attended the launch of Mat’s book at the Anzac Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park last Thursday, with proceedings including addresses from MC, Ray Martin OAM; Anzac Memorial Senior Historian and Curator, Brad Manera; Director of Australian War Memorial, Matt Anderson, PSM (via video); The Consul-General of Japan in Sydney, Kiya Masahiko; Member for Riverina, Michael McCornack, MP; and Cowra Breakout Association Secretary, Graham Apthorpe.

Australian Seniors News had the opportunity to interview Mat, providing some exclusive insight into the events that unfolded 78 years ago.

ASN: Mat, could you start by talking a bit about how the POW camps in Australia came to be?

Mat: Yeah, absolutely. So, in 1941 when Australia was fighting in North Africa against the Italians, we realised that we were taking a lot of Italian prisoners, and there was a need to put them somewhere. One of the things that surprised me doing the research for this book was how many prisoners were actually sent back to Australia. I thought they would have been just sent to Europe or the nearest allied base. But if we captured prisoners, it was considered that we had to look after them. So, Australia started establishing prisoner of war camps.

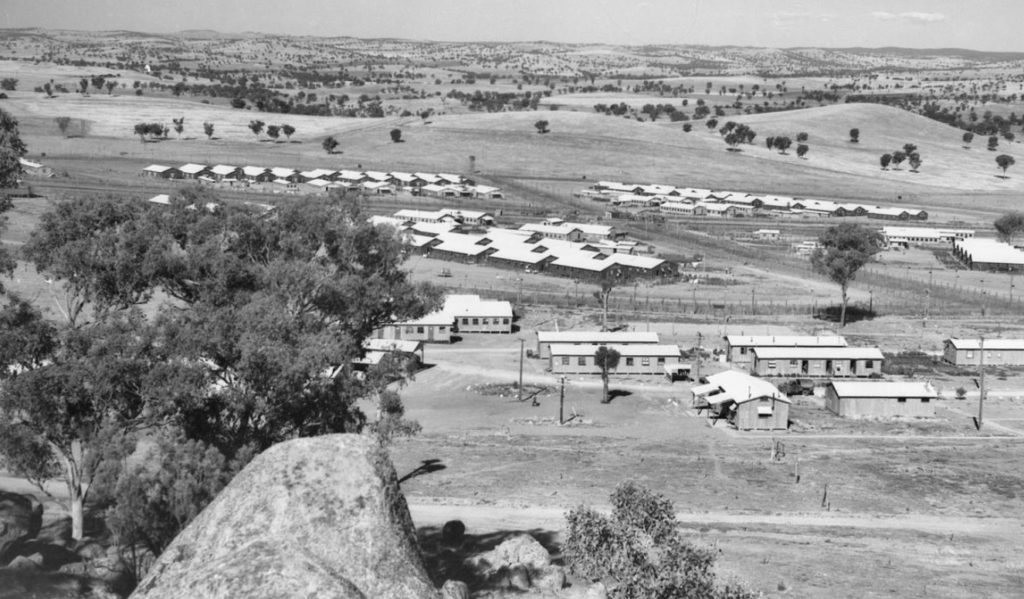

Just about every state in Australia had a prison camp, and the main one in New South Wales was in Cowra. In 1941, there were two programs that ran side by side. There was the prisoner of war program for combatants who’d been captured on the battlefields, and there was a program for civilian internship. Any civilians that were considered to be security risks were rounded up and put in camps. So these were people of German or Italian descent living in Australia

But then when war with Japan started, they were much stricter with the Japanese because they felt that the Japanese people were much more fanatical than European people. There was also a lot of racism, and so all Japanese in Australia had to go in internment camps effectively.

ASN: What were the conditions like in the camps?

Mat: Not really. There were international conventions that governed how people had to be treated, and these would eventually become the Geneva Conventions after the war. Australia was a good citizen of the world and followed those requirements.

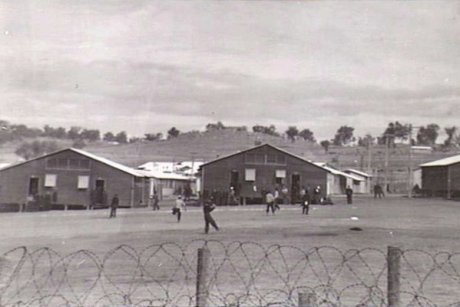

But focusing on the POWs, the conditions were actually really good in the camps. If we looked at Cowra for example, the camp was purpose built for prisoners of war. They slept in sleeping huts which had about 25 men in each hut. They were warmed with a fireplace. The prisoners were given clothing and blankets. They were given a heap of great food. In fact, 3,500 calories a day, including lamb from Cowra. Cowra lamb is still considered some of the best in Australia. They ate fish that was so fresh they could make sashimi with it. They could grow their own vegetables. They were given recreational opportunities, and so they built a baseball field in the camp, including a huge net to catch foul balls. They built a sumo wrestling ring. They built a theater where they put on stage shows.

Australia also had about 20,000 Australian prisoners being held by the Japanese. So Australian authorities were keen to demonstrate to the Japanese what a good job they were doing looking after Japanese prisoners, so that the Japanese would reciprocate with Australian prisoners.

ASN: What was the mentality of the Japanese at the time of the breakout? Why stage such an audacious escape attempt?

Mat: The key feature of it that we have to understand, is that even though it was a prison escape, it was not about freedom.

The Japanese military doctrine, even though it didn’t specifically say commit suicide instead of being captured, it effectively read that way. The shame of being captured was overwhelming, particularly for the families and communities.

When a Japanese man left home to go off and join the war, there was a big farewell for him from his family and community. But they weren’t celebrating the fact that he was going off to serve the empire. They were commemorating the fact that he was going off to die.

And so, the Japanese would generally not allow themselves to be captured. Japanese prisoners at Cowra were often airmen who had been shot down or sailors whose ships had sunk. They were a long way behind enemy lines and were often men who were either sick or had been wounded and couldn’t resist. And the next thing they woke up and they were in an Allied hospital being treated.

The Japanese called themselves ghosts because they were trapped between two lives. They were supposed to die a glorious death on the battlefield, but they were trapped between that and a life they could never return to in Japan because their families and communities had been told they’d been killed on the battlefield.

And so, when they staged the Cowra Breakout, it wasn’t about freedom – it was about battle. They saw it as their opportunity to rejoin the war and take the fight back to the Australians, to kill as many Australians in uniform as they could, to take over the camp and then hopefully at some stage, be killed and meet that noble death that had been so far denied and restore the honor that was lost by being taken prisoner.

ASN: Could you tell us a bit about the events leading up to the breakout?

Mat: One of the frustrating things about writing this book was that the Australian authorities were constantly aware that there was a threat of the Japanese doing something violent in the camp because everyone was talking about it. Korean labourers that were kept in the camp alongside the Japanese, but who didn’t like the Japanese would be working at the local railway depot and they would talk to the Australians while they were loading and unloading trains and they would say “the Japanese are definitely up to something”. There had been a riot at a camp in New Zealand at a place called Featherston in early 1943 and 48 Japanese had been killed. So there were lots of signs that there was trouble brewing in the camp, but the Australians, just for whatever reason refused to just acknowledge the danger.

And then in June 1944, a Korean who had been fighting alongside the Japanese, but again didn’t like the Japanese, came to camp authorities and said he had overheard the Japanese talking specifically about a plan to charge the barbed wire and try and take over the camp.

And so now the Australians had legitimate information that something was going to happen in the camp, and so that’s why they took some precautions. They installed machine guns, they made plans, and they decided that the camp was overcrowded. They decided the best way to make sure that nothing happened was to split the camp in half and send all the Privates to the camp in Hay.

But the frustrating thing was that they gave the Japanese three days’ notice. On Friday the 4th of August at lunchtime, they called the camp leaders in and they said on Monday we are moving half of the men to another camp, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Just get ready for it.

So, Friday afternoon the Japanese got together in all their huts. They said here’s what’s happening, we can’t let it happen, it’ll be a huge blow to us all if we’re separated, we have to do something. And so they said well, we’ve been talking about this uprising for a long time, now we have to make it happen.

They began securing baseball bats and knives and bits of wood and whatever else they could assemble. And then at two o’clock on the Saturday morning, they launched this huge outbreak from the camp.

ASN: Can we talk a bit about the breakout itself? What strategy did the Japanese use?

Mat: There were four groups of between two and three hundred men. There was a big road that went down the middle of the camp which was called Broadway, and so two of those groups broke into Broadway with the intention of attacking the guards at the North and South ends of the camp. Now they were not successful at all because when they got onto Broadway, which was sort of hemmed in with big fences, the guards at both ends opened fire. A lot of men were killed on Broadway.

Another group went to the eastern fence and climbed over, throwing blankets over the barbed wire. The fences were only about five feet high. F Guard Tower was the only protection along that entire eastern side of the camp, and it had one man in it, and he was only armed with a little submachine gun and his personal rifle. How was he going to stop a breakout? About 300 men charged defenses on that side, and most of them got through the fences.

But the main point of attack was a machine gun on a truck trailer just outside the wire on the other side of the camp, and the Japanese had noticed that the gun was not manned overnight. And so, the Japanese wanted to capture that gun turn it on the Australian Guards. The main group of about 300 men charged towards that.

Two Privates, Jones and Hardy, were in their early 40s. They’d served in the First World War but now they were too old to serve in the Second World War. And so here they were in the Garrison Battalion. When they heard the breakout begin, they threw on coats over their pajamas and pulled on their boots without even doing up the laces, and ran for the gun. It was literally a race for the death – who was going to get there first?

300 Japanese were screaming and trying to climb over the fences towards the gun, but Jones and Hardy got there first and opened fire on the Japanese. A lot of Japanese were killed or wounded but there were too many of them. A couple of hundred survivors swarmed all around the machine gun and Jones and Hardy at that point could have been forgiven for abandoning their posts because they were about to be overrun. But instead, they stayed on the gun and they kept shooting. And then when it was obvious the Japanese were going to take over the guard, they dismantled a key component of the machine gun so that the Japanese couldn’t use it against the Australians. Eventually, the Japanese swarmed all over the trailer and killed them both – beat them to death on the trail.

Jones and Hardy, about ten years after the war, were awarded the George Cross, which is basically the highest non-combat award you can get. It’s the non-combat equivalent of Victoria Cross. Because the Japanese couldn’t get the gun into operation, that destroyed their entire plans for taking over the camp, and so about 350 Japanese who managed to get through the wire now didn’t have much to do. They basically ran off into the Bush. It took nine days to round up the last of the escapees. But by the time they rounded them up, 234 Japanese had been killed and five Australians.

ASN: So, the Japanese soldiers were sort of on the run for nine days. There must be some interesting stories during that time period?

Mat: There are some absolutely fascinating interactions between the town people and the escaped prisoners. There were some unsavory incidents. Like, a young bloke rang the camp and said there were a bunch of Japanese just sitting near the camp not really doing anything, and a group of soldiers just walked down and shot all of them, didn’t give them a chance to surrender.

There was another case where an Australian civilian went out. He said to the police he was hunting for rabbits, but it seems pretty obvious that he just wanted to get involved in the excitement. He went out with his young son, armed with a shotgun, and came across a group of Japanese and fearing for his safety, he ended up shooting dead two of them. There’s one thing for guards to be shooting prisoners trying to escape, but for civilians to be shooting unarmed prisoners with a shotgun was pretty dangerous.

But there’s also some very positive interactions as well. A lot of farmers took pity on the Japanese. The Japanese were very strict in the policy when they broke out that no civilians were to be harmed, that the attack was only against men in uniform. There was one farmer that heard a commotion outside his house. When he went out to have a look what was going on, he saw two Japanese prisoners out there, and so he invited them into the farmhouse. And while his wife gave them a meal of chops from last night’s dinner, he called the camp and they spent 40 minutes just chatting and one of the Japanese gave him his belt buckle as a souvenir to say thank you.

ASN: Wow. What an absolutely fascinating story Mat. Thanks for sharing with us.

Mat: Thank you!