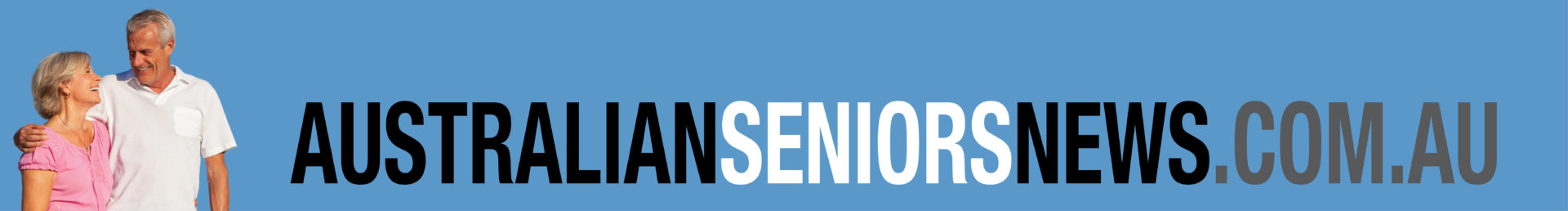

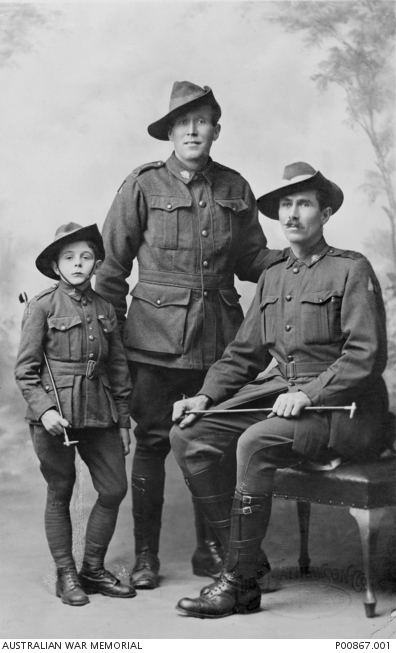

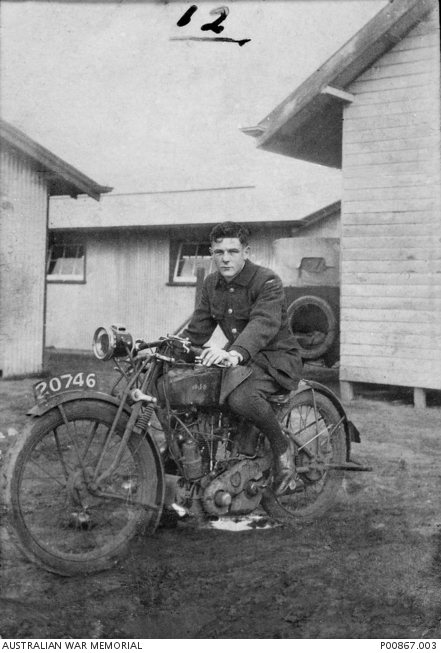

Honore (Henri) ‘Digger’ Heremene c. 1919

It was Christmas Day 1918, and the men of the Australian Flying Corps 4 Squadron had just sat down to enjoy a sumptuous Christmas lunch when a small French boy wandered in to the airmen’s mess at Bickendorf Air Base in Germany.

Cold, hungry, and alone, the boy invited himself to the feast, sharing in the festivities as the men celebrated their first Christmas since the Armistice was signed on the 11th of November 1918.

He introduced himself as Honore, but the Australians couldn’t pronounce it, so he became known to them as Henri, and was nicknamed “Little Digger” or “Digger”.

His parents had been killed during the war, and he had survived four years on the battlefields of the Western Front, aided by the kindness of allied soldiers.

He was “adopted” by the Australians and quickly became part of squadron life, skating and joking with the men, catching rats, and hitching rides on planes. They chose Christmas Day as his birthday, and it was the one he would use for the rest of his life.

One of the men, Tim Tovell, became his unofficial guardian, giving the boy his name and smuggling him back to Australia, where he raised him as his son.

Australian War Memorial Historian Dr Meleah Hampton said the story of how Henri Hermene Tovell was adopted by the men of the Australian Flying Corps and smuggled into Australia was remarkable.

“He is one of those little kids who is a true casualty of war,” Dr Hampton said.

“His father was killed in the early weeks of the war, possibly as a soldier, and his mother – and possibly a sister – were blown up and killed when the Germans shelled their house.

“From what we can work out, he had been going from unit to unit, spending a little bit of time with them, getting food and whatever, before moving on to the next one, and that’s what he was doing when he wandered into to the Australian Flying Corps mess on Christmas Day 1918.

“We don’t know when he was born, and we’re not even sure what town he really came from, or what his surname really was, or anything.

“He didn’t know how old he was when he arrived in the Australian Flying Corps mess, but the Australian doctors said they thought he was about nine years old at that stage.”

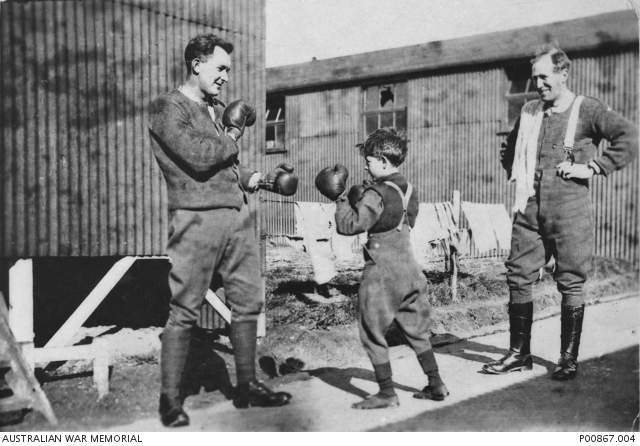

and Private Timothy William Tovell (right) with Henri (left). May 1919..

The boy became something of a mascot for the squadron, and the men determined to smuggle him home to Australia. Tovell wrote to his wife, Gertie, telling her that he didn’t think one extra in the family would make that much difference.

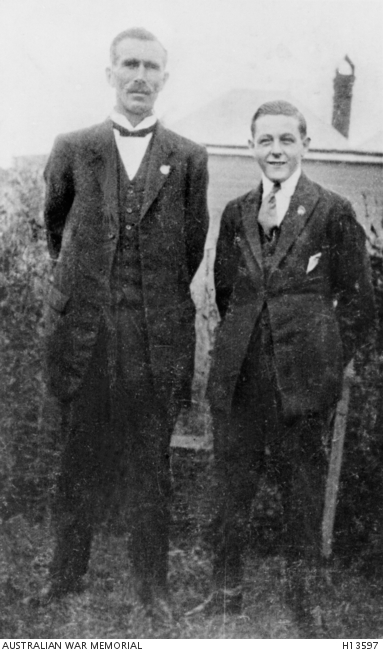

“Tim Tovell was an air mechanic who had recently joined 4 Squadron,” Dr Hampton said.

“He has quite an interesting story as well. He was English, and he got married in 1911, but his lungs were no good.

“The doctors thought dry air would be good for him, so he migrated to Australia with his new wife, and they set up home near Dalby in the Darling Downs in Queensland.

“He gave his age as 38 when he enlisted in 1917, but I think he might have been closer to 40.”

He was a husband and a father, so when this little boy walked into the airmen’s mess, he really felt for him, and they formed quite a bond.

Henri in a tailored AIF uniform made for him in London at the expense of the squadron’s members.

“Tovell determined that he was going to bring the boy home to Australia, and that created quite a stir.

“The French and the English authorities didn’t want him to go. They wanted him to go and live in an orphanage, so the Australians decided to smuggle him home with them on a troopship. They carried him on board in a kit bag, and then hid him in a bag of bread, or a bag of oats, until it was too late to turn back.

“On the way home, another passenger on the ship happened to be the Premier of Queensland, and he was able to arrange for the paperwork for the little boy to get off the ship and enter Queensland.”

Tovell and his wife, Gertrude, adopted the boy and he lived with them and their family in Queensland. Their four-year-old son, Timmy, had died in 1919, while Tovell was overseas.

“It’s a really interesting story,” Dr Hampton said.

“This little French boy was all alone and one man said, ‘Nope, I’m not going to watch him walk out the door,’ when plenty of people had watched him walk out that door before.

“There is a story that suggests a British artillery officer became quite close with him at one point as well, but he was killed-in-action too.

“He’s only young when he wanders into the airmen’s mess, and he can’t remember names and ranks and surnames and all of those sorts of things, so it is difficult piecing it all together.”

“He can’t explain to the Australians who he is, where he came from, and who these other people were that looked after him, so we’ve never really been able to work out exactly who he was, and I don’t think he really ever knew who he was either.

“Tim Tovell was a steady and strong person for Henri to cleave to. He really needed that, and I think Tovell was happy to be the person that he needed.”

Henri became a much loved member of the Tovell family, but his story has a tragic ending. He was killed in a motorcycle accident in Spring Street, Melbourne, in May 1928.

He had moved to Melbourne in the 1920s to work as a mechanic with the Royal Australian Air Force like his adopted father. He had been staying at Point Cook, and applied to join the air force, but because he was a French citizen, he was stopped from doing so by the French High Commissioner.

Despite not being a member of the air force, Henri was buried with military honours at Fawkner Cemetery in Melbourne.

The story of the “Little Digger” resonated with the public, and The Argus newspaper launched an appeal to pay for a memorial headstone to be erected over his grave.

The headstone featured a statue of the young Henri as he looked when Tovell and the men of the Australian Flying Corps first met him. It disappeared in the 1950s and a new stone was paid for by the RAAF Association of Victoria and the Federal Government.

Tovell and his wife, Gertie, were never told about the desecration. It was thought it would be too much for them.

This article first appeared on The Australian War Memorial website, author Claire Hunter.